1780

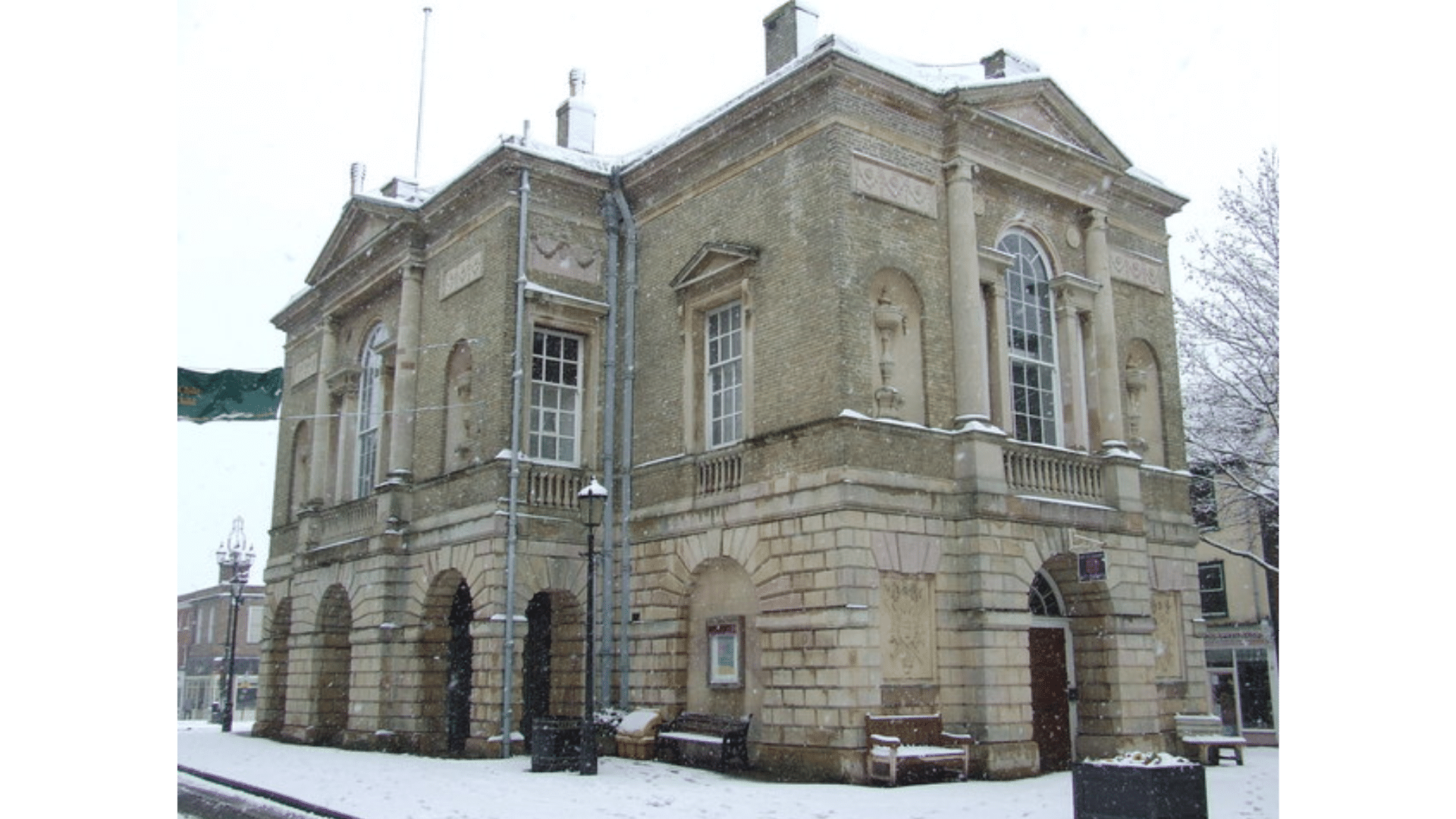

The original market cross was a medieval timber building which was used for theatrical performances during the annual Bury Fair. By the late 18th century it was decided that a town of Bury’s stature demanded a more dignified building and the fashionable London architect Robert Adam was commissioned to design a replacement. Adam’s Market Cross, completed in 1780, still stands today and its façade is adorned with carvings of theatrical masks and musical instruments. Although this was a vast improvement on the previous building, the new Market Cross was still too small to cater for the potential audiences and in 1818 the lessee, William Wilkins asked the council if he might ‘take the stage, box fronts, seats…traps, machinery, wings etc’ to a new site in Westgate Street and there build a theatre ‘of ample dimensions and elegance corresponding to the other public buildings of the place’ at a cost of £5000.

Market Cross

Keith Evans / The Guildhall / CC BY-SA 2.0

1815

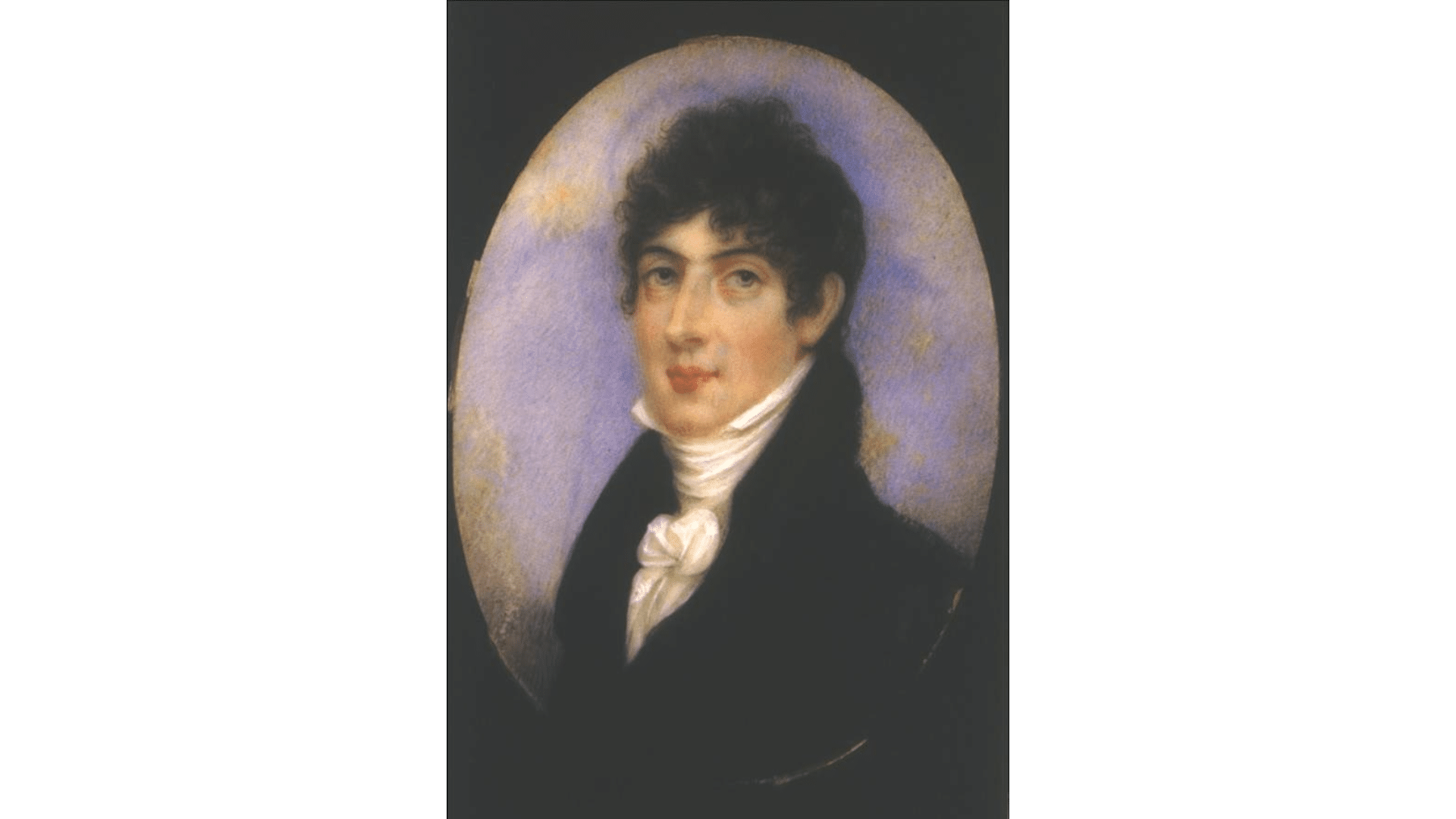

William Wilkins Senior took over the lease of the Norwich Circuit of Theatre in 1757 [theatres were in Norwich, Cambridge, Colchester, Bury St Edmunds, Ipswich and Great Yarmouth) and he enlisted the help of his son to renovate or redesign all of them over the next fifteen years. In 1815, on his father’s death William Wilkins junior took over the running of the Circuit. William was a scholar and architect who had studied at Cambridge University and travelled across Europe. It was while on this Grand Tour that he visited the ancient amphitheatre at Taormina in Sicily which was to inspire his design for the theatre at Bury St Edmunds.

Wilkins went on to design many famous buildings including the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square and buildings at University College London and Cambridge University. Theatre Royal is the only original building from the Norwich Circuit to survive and is now the only Regency theatre in the country.

Date Unknown. Portrait Miniature of architect William Wilkins (Junior)å

Private Collection [TRBSE have permission from W Wilkins]

1819

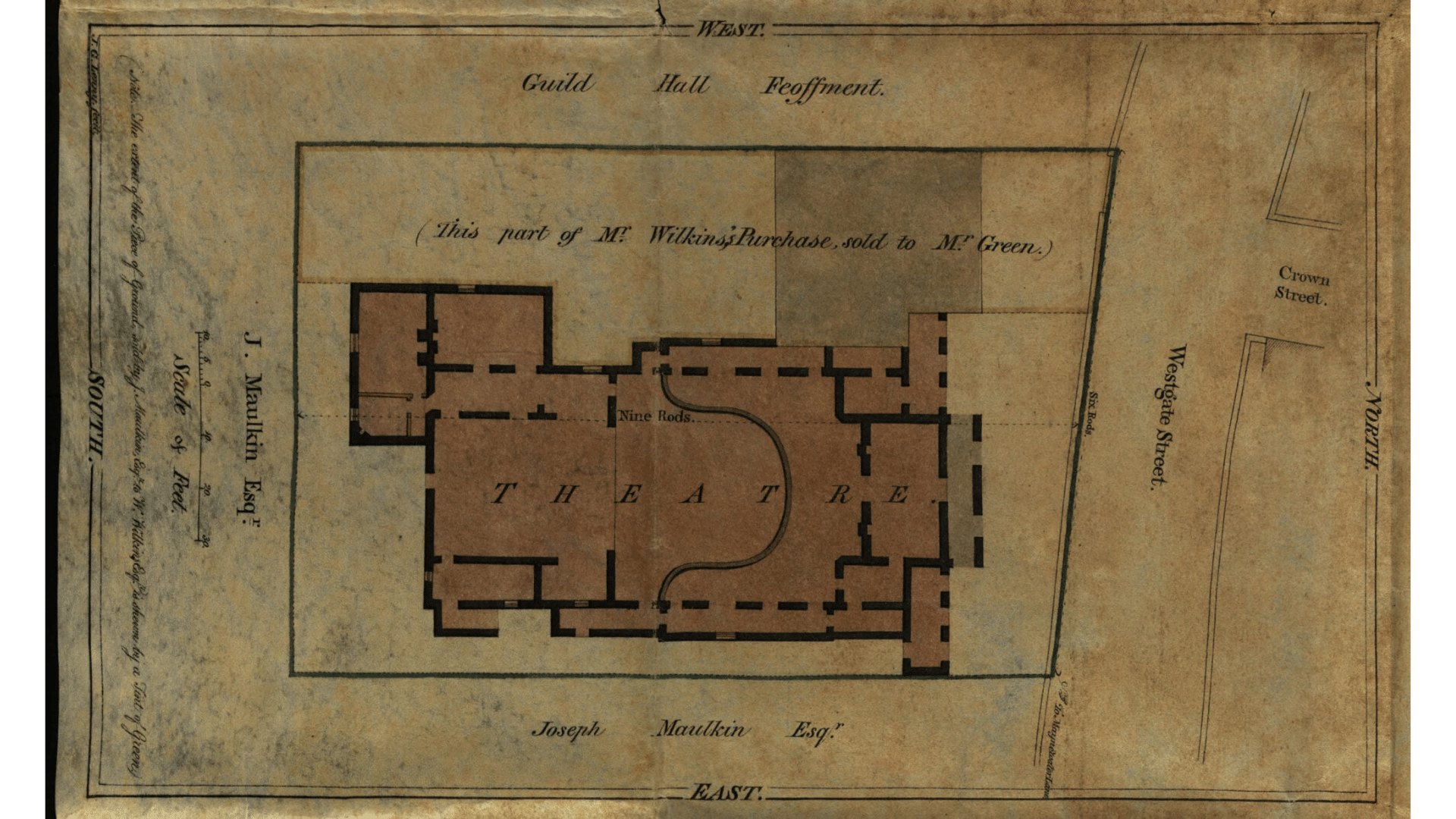

819 Deed plan of the Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds

Suffolk Record Office E4/29/1-18 CREDIT: Suffolk Archives

1819 Deed plan of the Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds

Suffolk Record Office E4/29/1-18 CREDIT: Suffolk Archives

1821

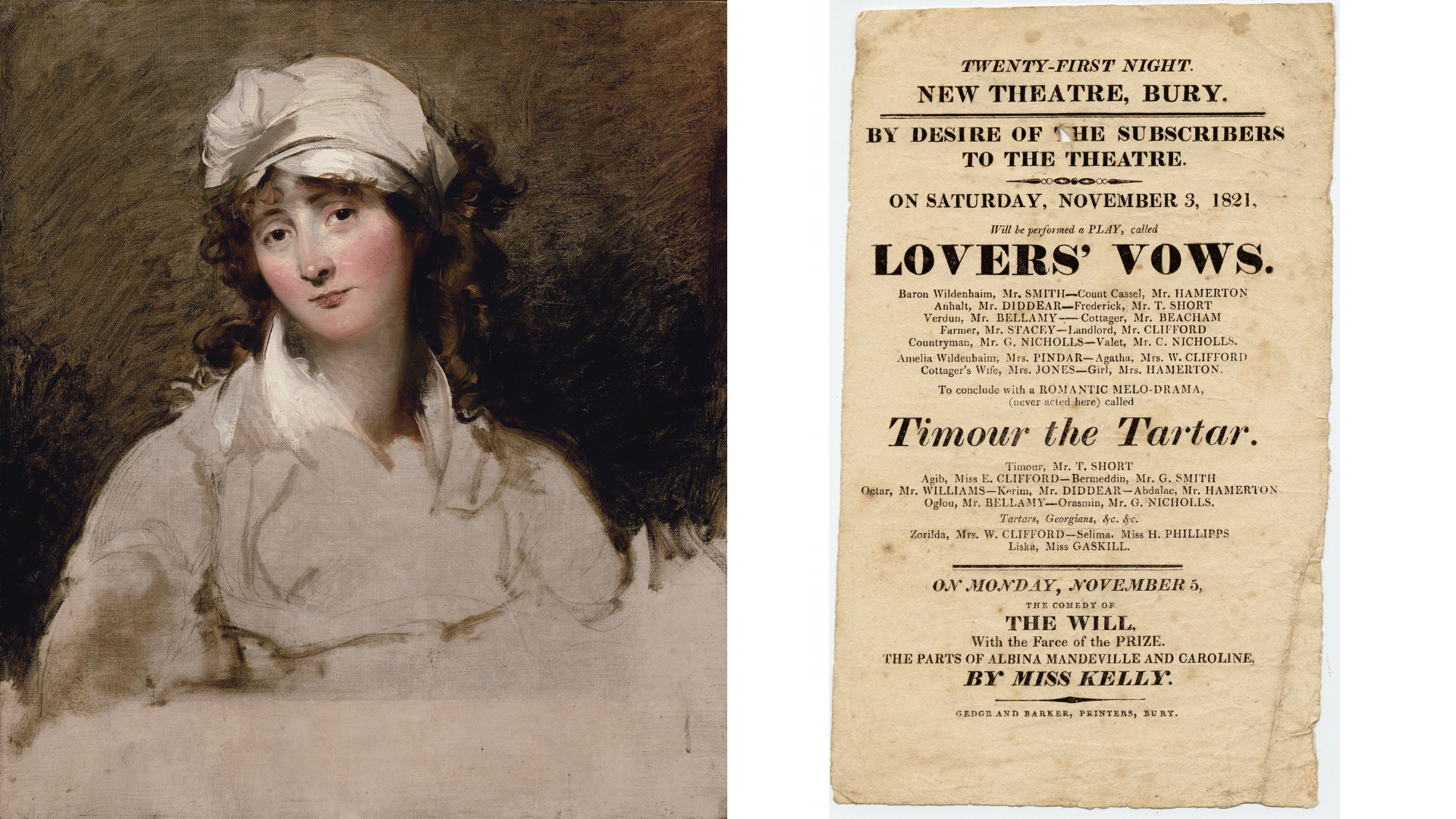

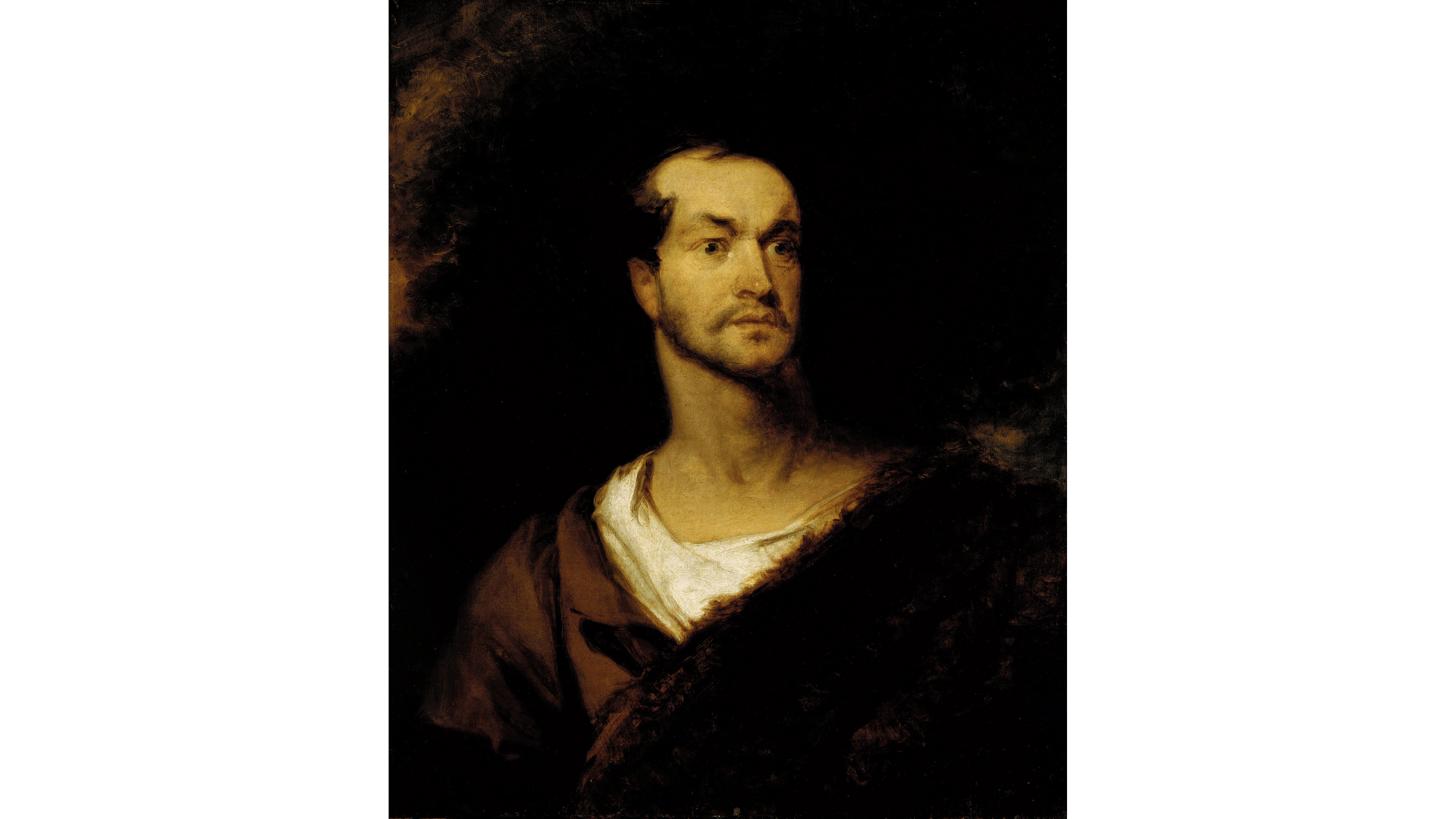

Amongst the plays performed at the New Theatre in the 1820s was ‘Lover’s Vows’ by Elizabeth Inchbald (1753-1821), who as a young girl had attended performances at the Market Cross. Elizabeth’s family lived at nearby Stanningfield and had many theatrical friends; her brother even became an actor at Norwich, but when Elizabeth declared her wish to pursue a theatrical profession, it was prohibited, prompting her to run away to London where she eventually achieved her dream of becoming an actress. While she met with modest success on the stage, it was not until 1784 that she found her real talent lay in writing plays, for which she became famous. Although Inchbald died shortly before the first performance of her play Lover’s Vows at Theatre Royal in 1821, her work inspired many other writers, including the young Jane Austen whose early ambition was to become a playwright and who notably mentions the play in Mansfield Park.

1796 Mrs Joseph Inchbald, by Thomas Lawrence

Elizabeth Simpson Inchbald *oil and black chalk on canvas *71.1 x 63.5 cm. *circa 1796

Lovers Vows playbill

Wikimedia Commons and Theatre Royal Bury St Edmunds collection

1828

In 1828 William Macready, one of the most celebrated actors of the day appeared at the theatre. He performed a different role every night for four nights; ‘Othello’, ‘Virginius’, ‘Macbeth’, ‘William Tell and ‘Hamlet’.

‘Speaking generally of Mr Macready, we should describe him as strongest in weakness, and weakest in power. He has extraordinary command over his features, but his voice is defective, and he moves us more by his fine touches of nature than by his bursts of violent passion. His conceptions are always chaste, but they have not the vigour and originality of Kean’s. There is a t times a stiffness in his manner, and a monotony in his undertone which ought to be remedied. He walks the stage with great dignity, and his attitudes are all of them fine enough for statuary, but sometimes smack a little of the posture of the posture-master. Above all (or rather most indispensable of all) he is very correct – a quality which we should be glad to see imitated by one or two of our company.’

1793-1873 William Macready

Macready’s Reminiscences, and Selections from His Diaries and Letters p.332 [google books] Wikimedia Commons William Charles Macready as William Tell MET ap06.195 Bury and Norwich Post 19 Nov 1828

1828

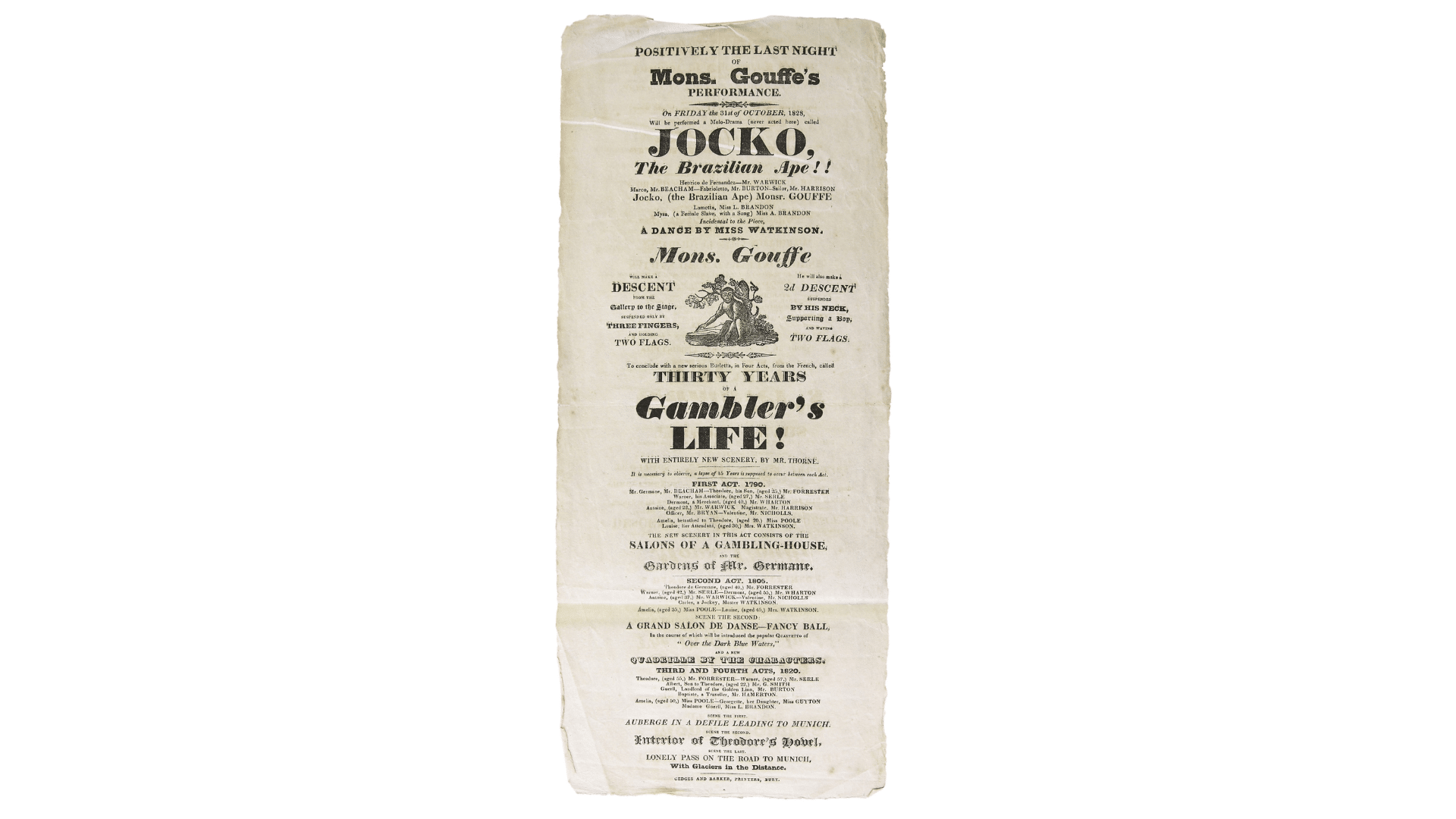

At the same time as the serious tragedian William Macready was treading the boards at the theatre, another, very different act appeared. This was ‘Monsieur Gouffe’ the ‘man-monkey’, a talented performer who would imitate an ape by running around the box fronts knocking off people’s hats, kissing women and performing acrobatic feats. His signature move was to slide on a zip wire from the gallery down to the stage, supported only by three fingers and carrying a child on his back. While the real identity of Monsieur Gouffe was uncertain, recent research has suggested that Gouffe’s real name was John Hornshaw, an illiterate Londoner who happened to catch the eye of the theatre manager Charles Dibdin with his incredible strength. Hornshaw toured the character of Gouffe around the country and to America developing the act to include hanging with his neck in a noose – a stunt that resulted in near death experiences on several occasions and was written up as a medical curiosity in the journal The Lancet.

1828 Monsieur Gouffe Playbill

TRBSE collection

1829-1903

Jean Davenport was daughter of T.D Davenport, lessee of Theatre Royal from 1846 to 1848. Charles Dickens met the Davenports in London, and it is widely thought that they provided the real-life inspiration for the characters of Vincent Crummles, the manager of a touring stage company and his daughter Ninetta in his novel Nicholas Nickleby (1838). Ninetta is billed as ‘the infant phenomena’, a child acting prodigy (despite the fact that she is, in reality, far older than her father admits), and in this there may indeed be some comparisons with Jean, who was performing mature lead characters from an early age. Only 17 when she played Juliet at Theatre Royal, she was already a veteran of the stage having made her first professional appearance at the age of 8. Having already toured internationally, in 1849 she relocated to America, where, she continued to act, but life off-stage proved just as dramatic – during the civil war she supervised the training of nurses and in 1861 played a part in foiling a plot to assassinate president Lincoln.

Jean Davenport (1829-1903)

Wikimedia Commons Jean Margaret Davenport c1850

1830

In 1830 the famous political orator and reformer William Cobbett visited the theatre to lecture on the causes of agrarian distress (rural workers had seen worsening pay and conditions for some years, which were to erupt later that year in the Swing Riots).

‘Mr Cobbett began by stating that his object was to submit his opinions upon the [agrarian] distress, its causes, and its remedies, which he had a right to do. Strange it was that this country, gifted with advantages beyond all others, and once the greatest and the happiest in the world, should now be plunged in distress so deep that she durst not display her anger to other Powers: but it was not wonderful that they who had brought her to this state should seek excuses to make the people believed it was not their fault’.

Several ladies were present in the audience and ‘the Second Lecture was announced to commence at five in the evening, for the convenience of the farmers, by whom the Pit was crowded, and the lower-boxes were for the most part occupied: there were a few ladies as on the preceding night’

1835

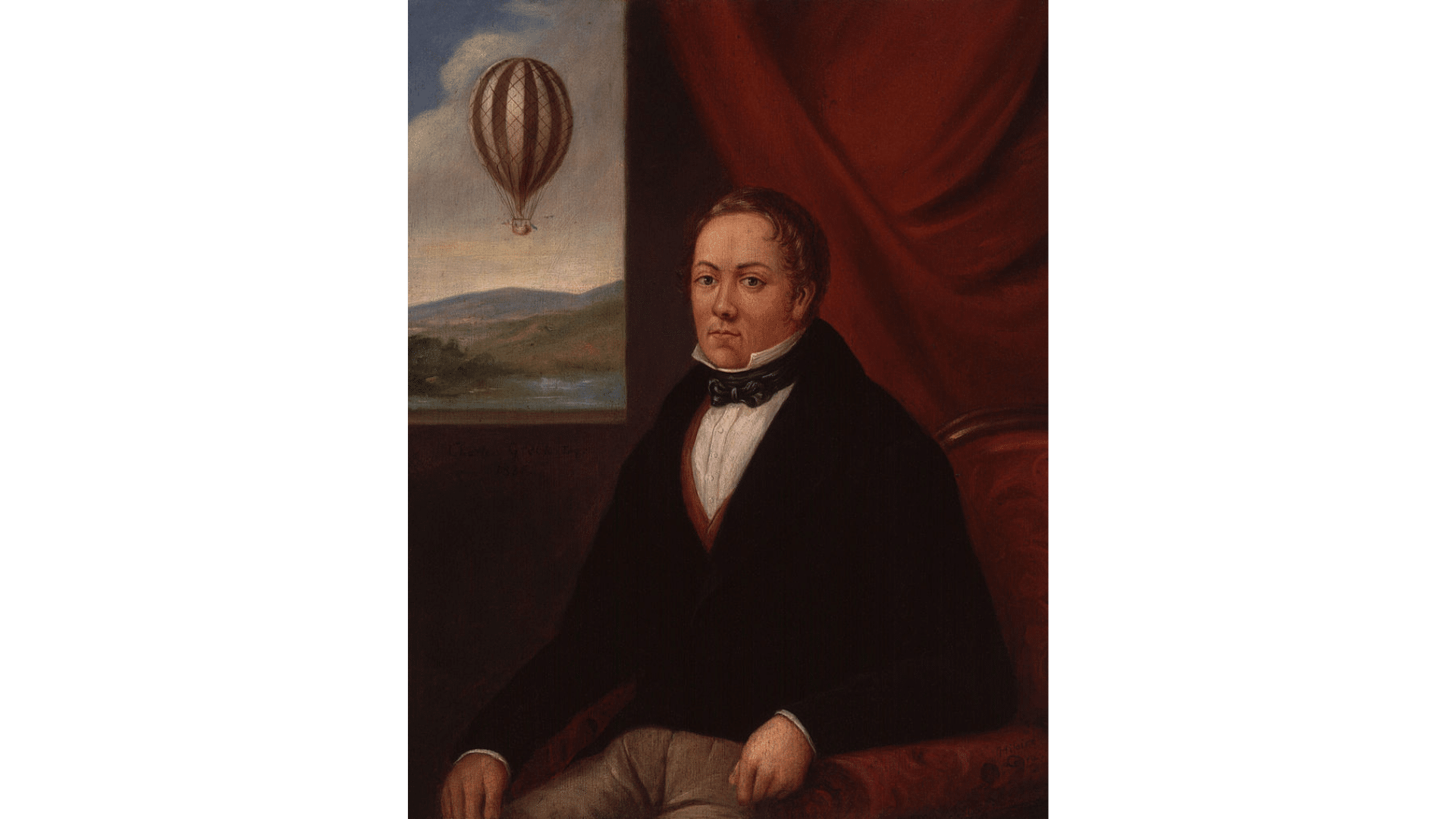

In 1835 Mr Green, described as a “prince of aeronauts” and two companions made one of the earliest balloon ascents in Britain from the Cattle Market in Bury St Edmunds. The technology was still notoriously dangerous. however Green enjoyed an excellent voyage on which they ‘opened a bottle of wine and drank the health of the King and Royal Family and Aldermen of Bury’at 4000ft. After landing at 28 miles away at Oakley Park, Diss, the intrepid trio travelled back to Bury by carriage ‘and received a hearty welcome at the Theatre’.

Hilaire Ledu, Portrait of Charles Green, 1835

Wikipedia Portrait of Charles Green by Hilaire Ledru, 1835

1845

Lucia Elizabeth Vestris was a highly talented operatic singer and dancer, who, having trained in Europe took the London stage by storm at the age of 23 (in 1820) with the first of many ‘breeches roles’ [roles in which women appeared in male attire – this was common in opera where many women sung the roles of young men]. These performances ensured her fame, but also a measure of notoriety with as many words written about her shapely legs as her talent! However, Vestris’ popularity ensured that she was able to afford to lease the Olympic theatre in 1830, and she set about a series of improvements that were to revolutionise the experience of theatre-going; tastefully redecorating the auditorium; finishing performances on time and seeing to it that classes did not mix to ensure the continued patronage of her fashionable audience as well as winning over performers by improving facilities backstage.

Other theatre managers took note of these developments; keen to silence the competition posed by Vestris and her husband Charles Matthews , William Macready hired them to act at Drury Lane and then added insult to injury by billing Vestris as a ‘supporting player’. To counter growing debts, the couple embarked on a series of provincial tours in the 1840s, which included visiting Theatre Royal Bury St Edmunds in September 1844, proceeds from which eventually allowed them to lease the Lyceum.

Madame Vestris visits in 1845

Wikimedia Commons Madam Vestris as Don Giovann

1845

With the relaxation of licensing laws theatre lessee W.J.A Abington renames the New Theatre as the Theatre Royal.

1874 – 1907

The Victorian period saw a wide variety of interestingly titled works, from melodramas such as ‘The Wife’s Secret’ and farce like ‘Pay for Peeping’ to the sweeping hit ‘The Corsican Brothers’, a gory play that so captivated the young queen Victoria that she saw it eight times.

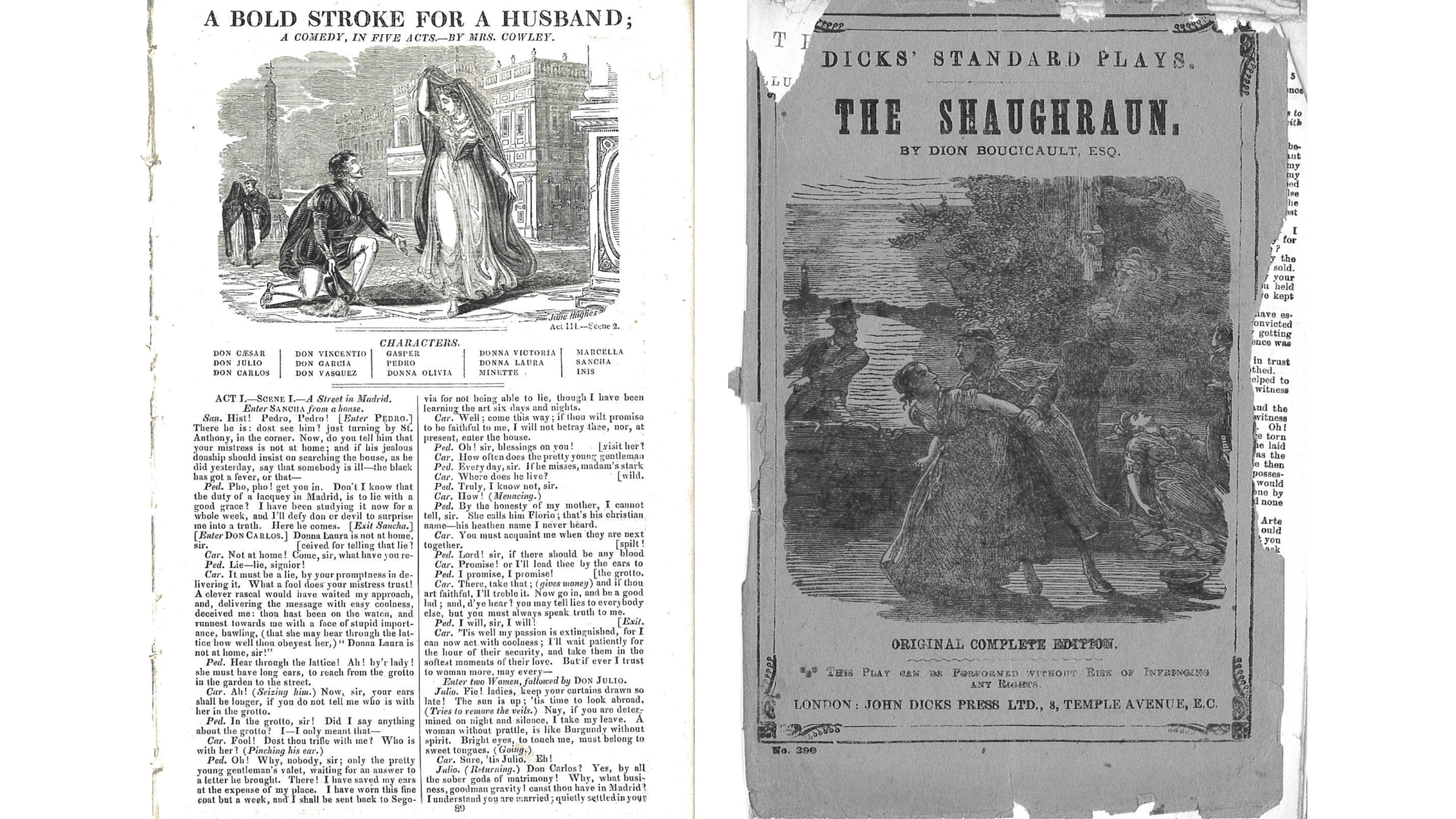

Between 1874 and 1907 John Dick published a series of popular plays – cheap editions of scripts intended for performance by amateur groups and theatricals at home, which were very fashionable during the Victorian period. Many of the titles issued in the series were of plays performed at Theatre Royal, including classic works by Georgian female playwrights such as Elizabeth Inchbald and Hannah Cowley.

1874-1907 Dick’s Standard Plays

TRBSE collection

1892

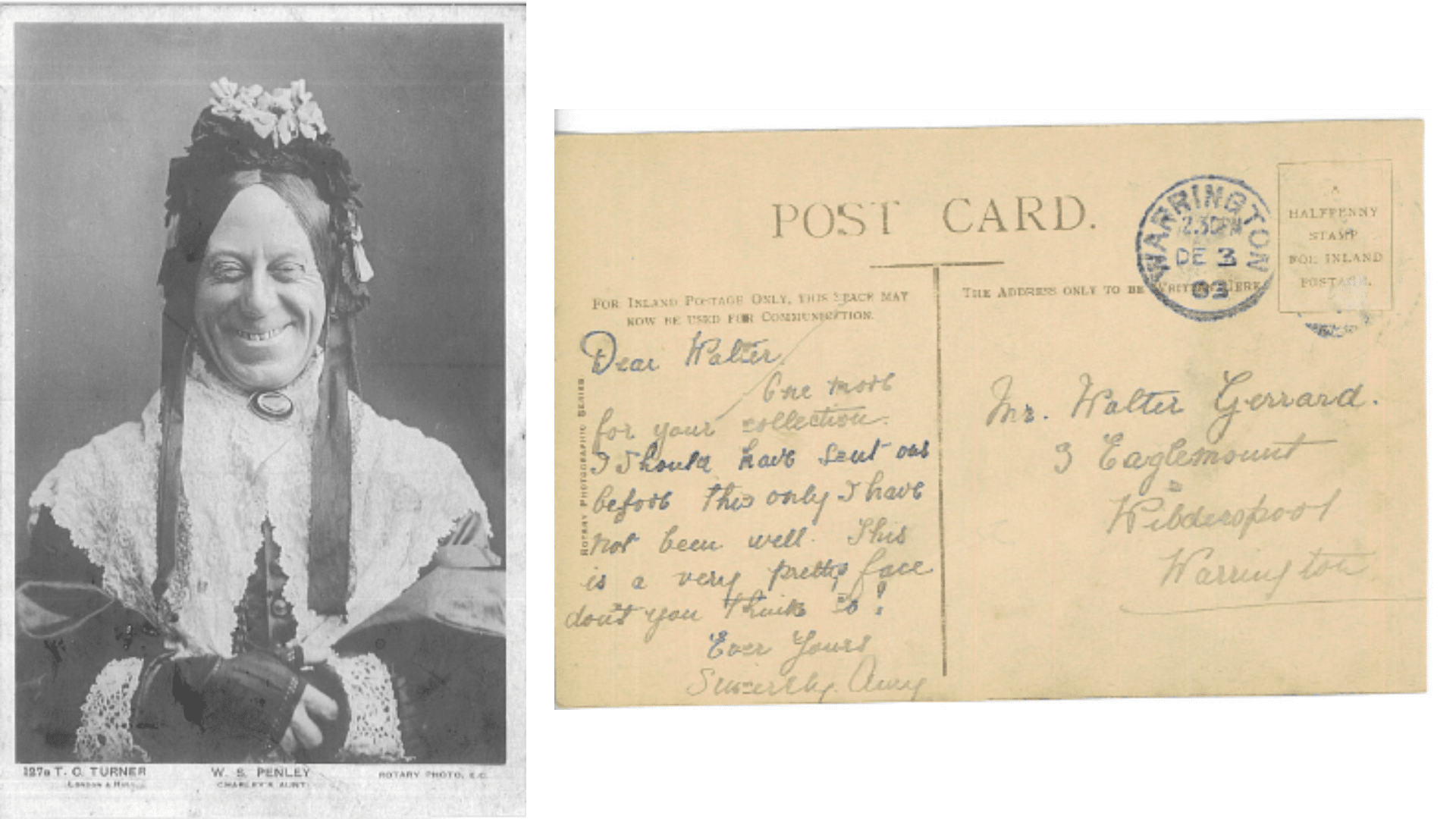

In 1892 Theatre Royal staged the world premiere of the play Charley’s Aunt, written by Brandon Thomas and starring W.S Penley. The idea was to test the play in front of a provincial audience before launching it on the London stage. Penley was a huge star at the time, but not everyone it seems that not everyone had heard of him; one local resident who worked behind the scenes at the theatre recalled that when Penley asked the theatre manager to make the booking ‘the manager wired to the lessee for instructions. The reply was “Who is he?”’ The show was an immediate success and went on to take London by storm – it was translated into numerous languages, souvenirs were produced and to date three film versions have been made.

1892 Charley’s Aunt postcard Front & 1892 Charley’s Aunt postcard Reverse

TRBSE collection

1893

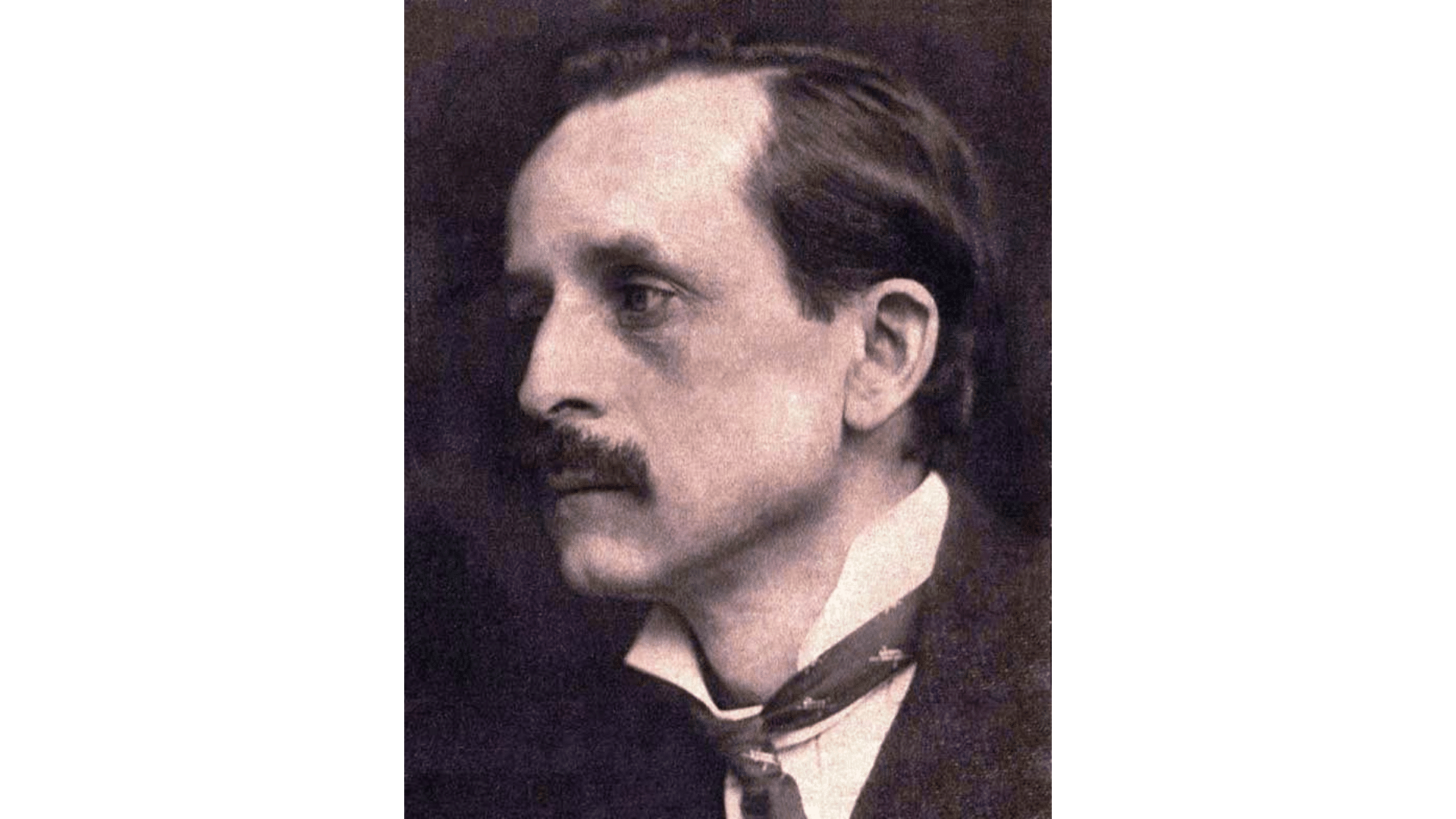

The success of Charley’s Aunt helped to enhance the reputation of Theatre Royal, encouraging the attention of other theatrical luminaries. In 1893 the playwright J.M Barrie visited the theatre as the guest of Mr and Mrs D’Oyly Carte. D’Oyly Carte was the producer of the hugely successful Gilbert and Sullivan operettas at the Savoy Theatre in London.

Incidentally, Nina Boucicault, daughter of the famous Victorian playwright Dion Boucicault played the role of Kitty Verdun in Charley’s Aunt when the play relocated to London in December 1892. Twelve years later she was to make her fame playing the title role in the first production of Barrie’s famous play Peter Pan.

1893 JM Barrie visits the theatre

Wikimedia Commons J. M. Barrie in 1901

1893

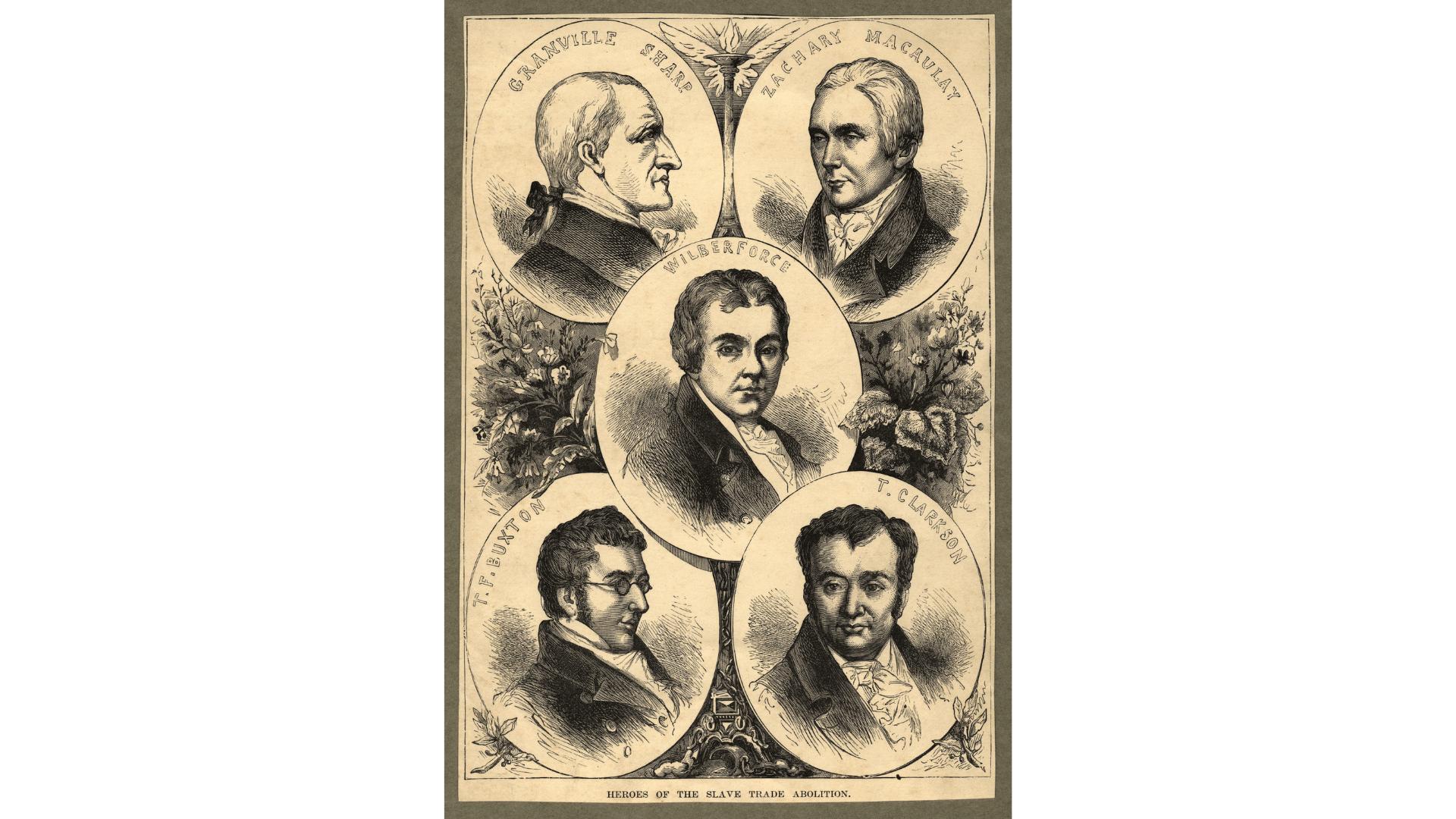

In 1893 a production based on Harriet Becher-Stowe’s book ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ appeared at Theatre Royal. The advertising boasted that the cast included ‘Fifty freed slaves’. There was perhaps an extra poignancy to this performance, given that Thomas Clarkson, one of the key figures of the Abolitionist movement lived just around the corner from the theatre – the plaque marking his residence can still be seen in St. Mary’s Square.

1893 Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Wikimedia Commons Heroes of the Slave Trade Abolition from NPG

1898

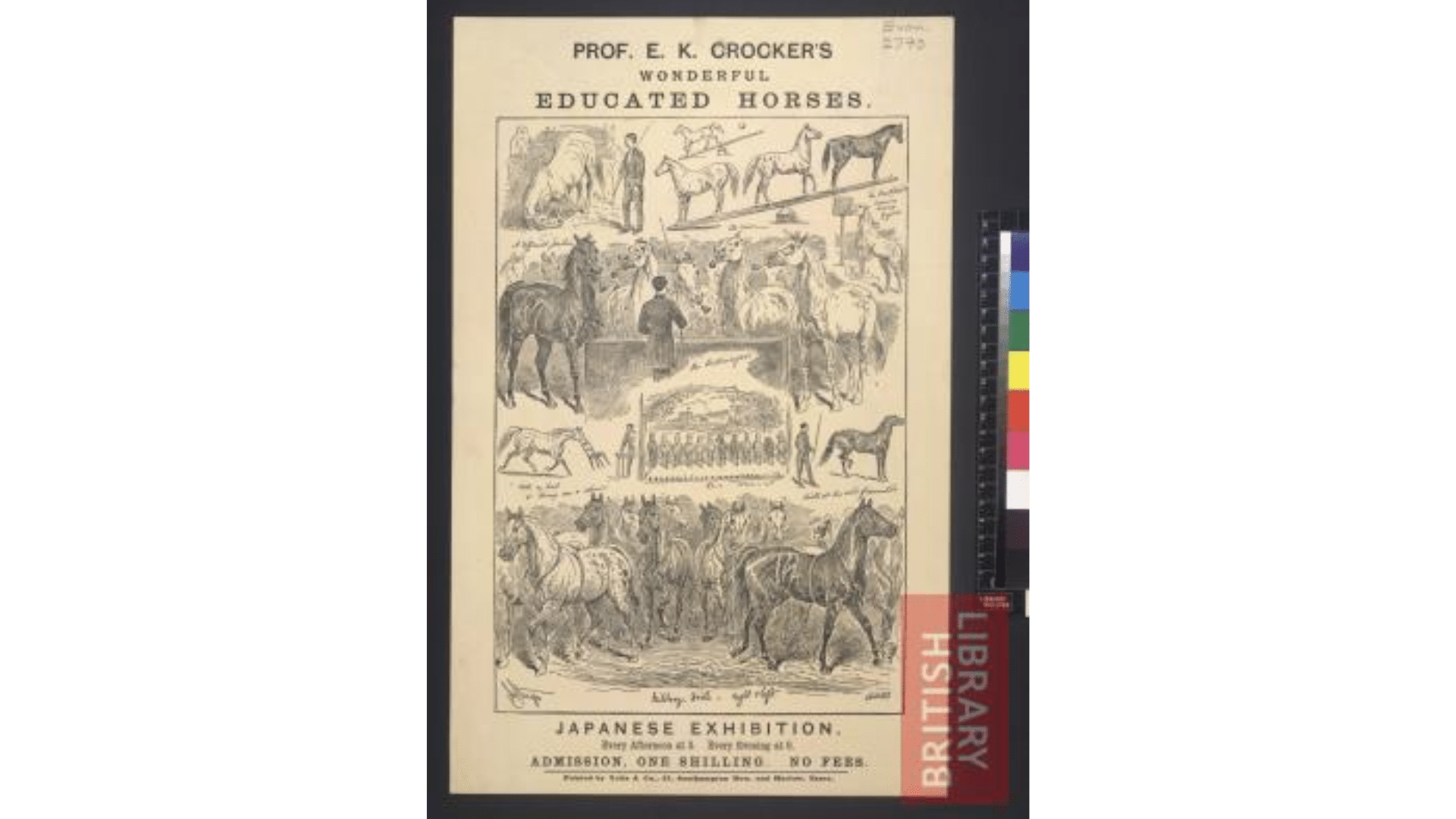

In 1898 The American showman and horse whisperer ‘Professor’ Esli K. Crocker made the first of several visits to Theatre Royal with his 30 ‘educated horses’. The horses performed a range of tricks from ‘solving’ mathematical problems and jumping over each other to dancing a waltz and giving a demonstration of bell-ringing.

1989 Professor Crocker’s Horses

1900

In 1900 the popular play ‘No Man’s Land’ written by the London based producer John Douglas arrived at Theatre Royal. As the local paper noted ‘the play has now been running for several years, and the success it has achieved is probably due more to the wonderful sensational scenes and effects’ than the ‘intrinsic merits of the plot… At our local theatre we have seen dramas in which steam roller, steam cranes, circular saw mills in fearsome rate of revolution played a prominent part, but we have not the slightest hesitation in asserting that all these pale before the extraordinary, remarkable and ingenious contrivance introduced in No Man’s Land.’ There is a tropical island setting ‘in the distance we see the ship “Enterprise” and in the foreground the land, and between we have the rolling sea, with its realistic heaving and the splashing of the waves against the rocks. The water is real and is contained in a large tank reaching across the stage, with [a] thick glass front, to show there is “no deception” and holds 3,500 gallons of the aqueous fluid. At the end of this act a typhoon arises with the awful suddenness peculiar to the tropics, and one of the most realistic storms ever produced in a theatre rages. The wind howls and shrieks with a reality so intense that we shiver in our seats, darkness falls quickly, the thunder roars and crashes, and the lightning is vivid to actuality, and then the curtain drops on this terribly real storm.’ The next use of the water tank -as an ‘old weir, a very pretty scene with the bridge at the back, and the water running over and falling from a height of several feet with a musical splash! splash! into the stream below. It is remarkably well done, and the climax is only reached when Bessie is thrown into the stream by the villain’s henchman and the heroine boldly dives from a height to effect her rescue. The scene is worked up to with fervour, and the whole house rose at the end and cheered and cheered again; in fact, they would have liked it all done over again.

1901

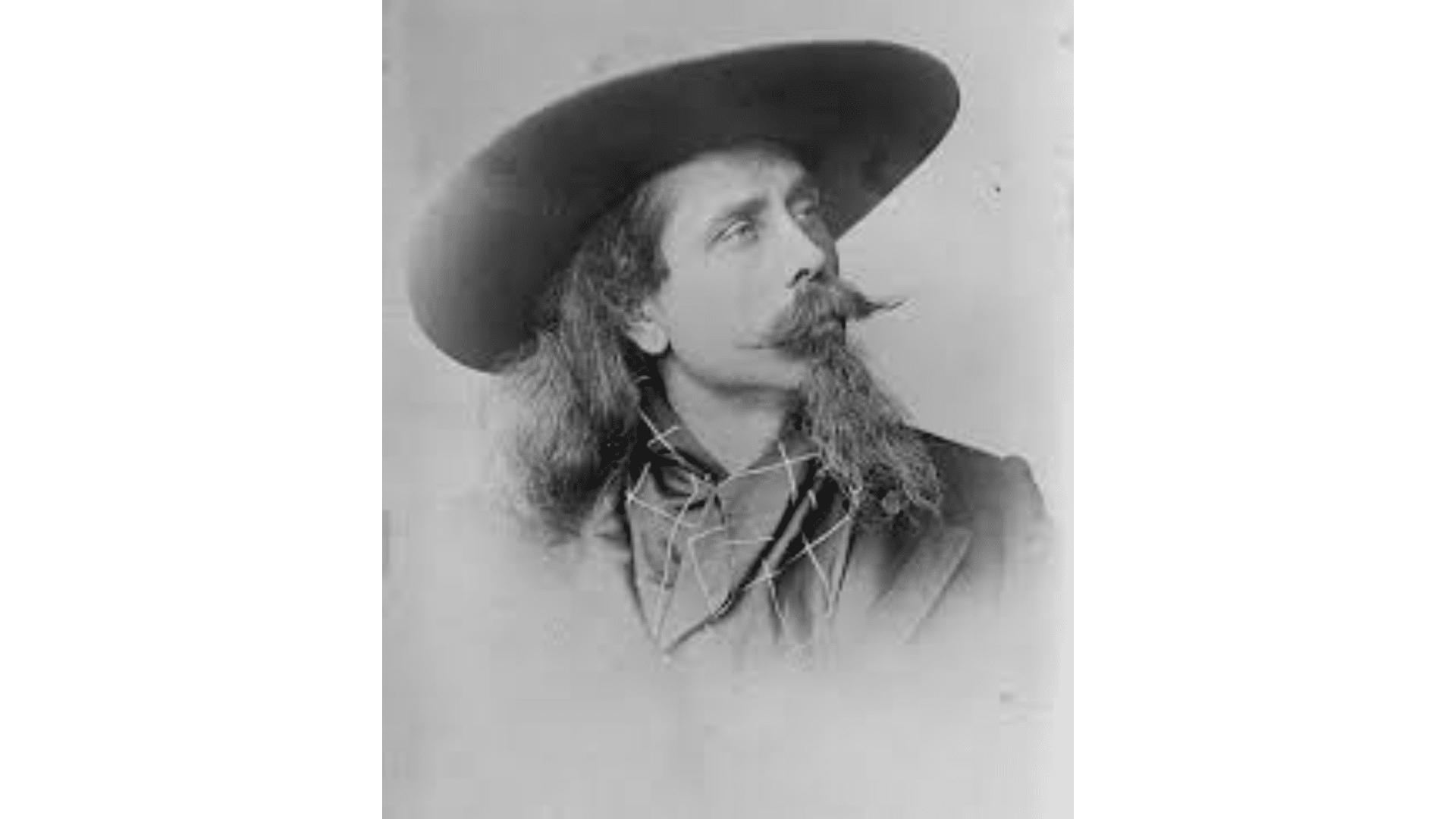

Samuel Franklin Cody was a Wild West showman (not to be confused with ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody) who toured Europe from the 1890s.

In 1898 Cody performed a play, written by himself, called the The Klondyke Nugget. This ‘spectacular American drama’ depicting ‘life as spent in the gold fields in Alaska’ was full of ‘wildly sensational incidents’ and proved a hit throughout Britain, appearing at Bury St Edmunds in November 1901. Cody used the proceeds from his theatrical work to fund his other love of aviation, a field in which he was an early pioneer – becoming the first man to fly an aeroplane in Britain in 1908.

1901 Samuel F Cody visits the theatre

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

1906

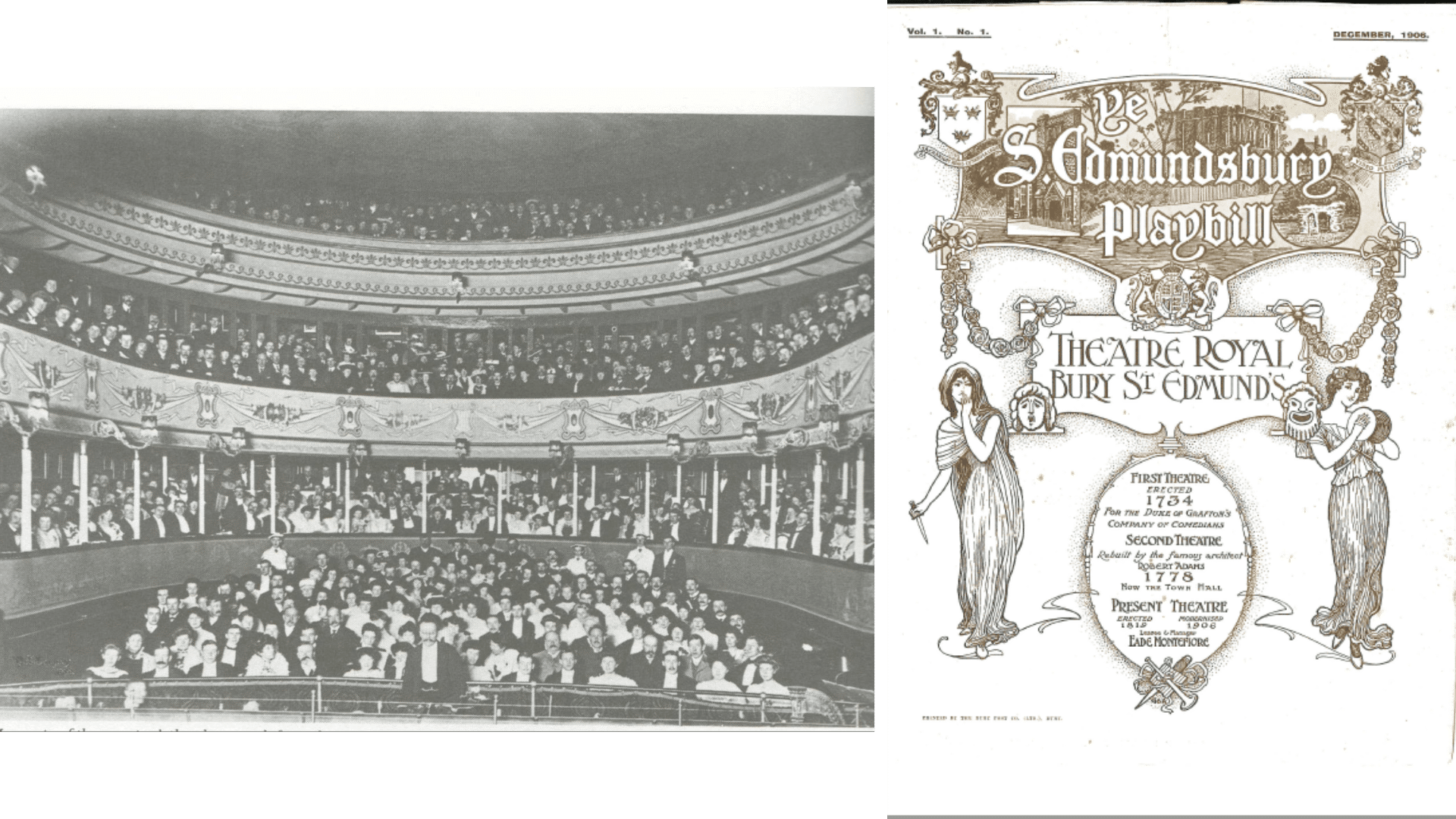

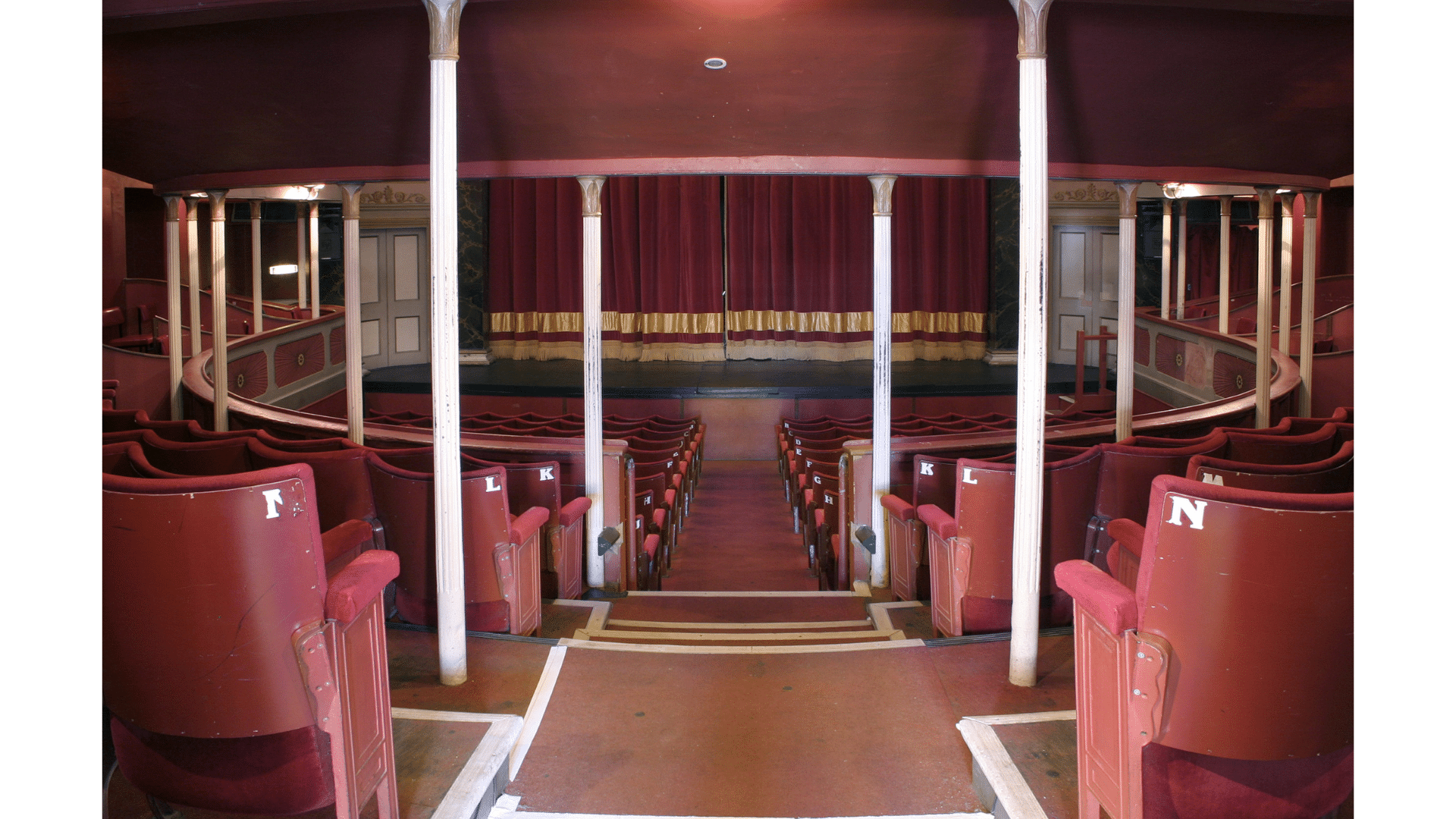

In 1906 the theatre was reopened after a period of renovation by new lessee Ede Montefiore – seen here at the front of the orchestra pit. Montefiore hired London architect Bertie Crewe to make the theatre more comfortable; adding carpets, crimson velvet seats and a bar on the first floor (now the Peter Hall Room). The image also shows how the rear box walls in the dress and upper circles were replaced with ‘half walls’ to allow standing room – when full the theatre could now accommodate up to 678 people.

1906 Reopening of the theatre

TRBSE collection. : SRO EE500/43/24 Report: 4 May 1908 Places of Public Resort – Exits

1906 St Edmundsbury Playbil

TRBSE collection

1910

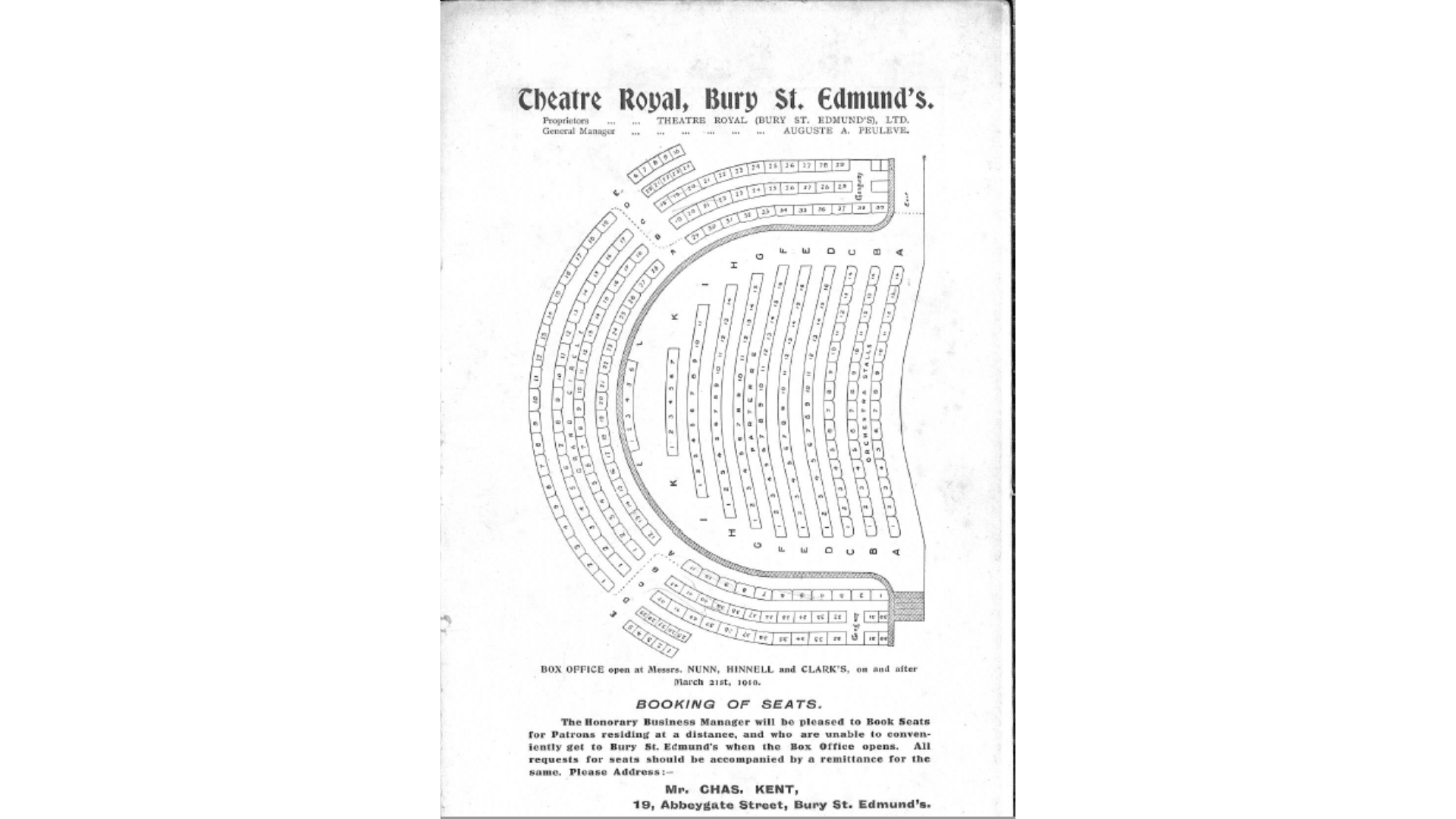

Seating plan from 1910 showing the auditorium – the pit alone accommodates almost 40 seats more than today!

1910 seating plan

TRBSE collection

1910

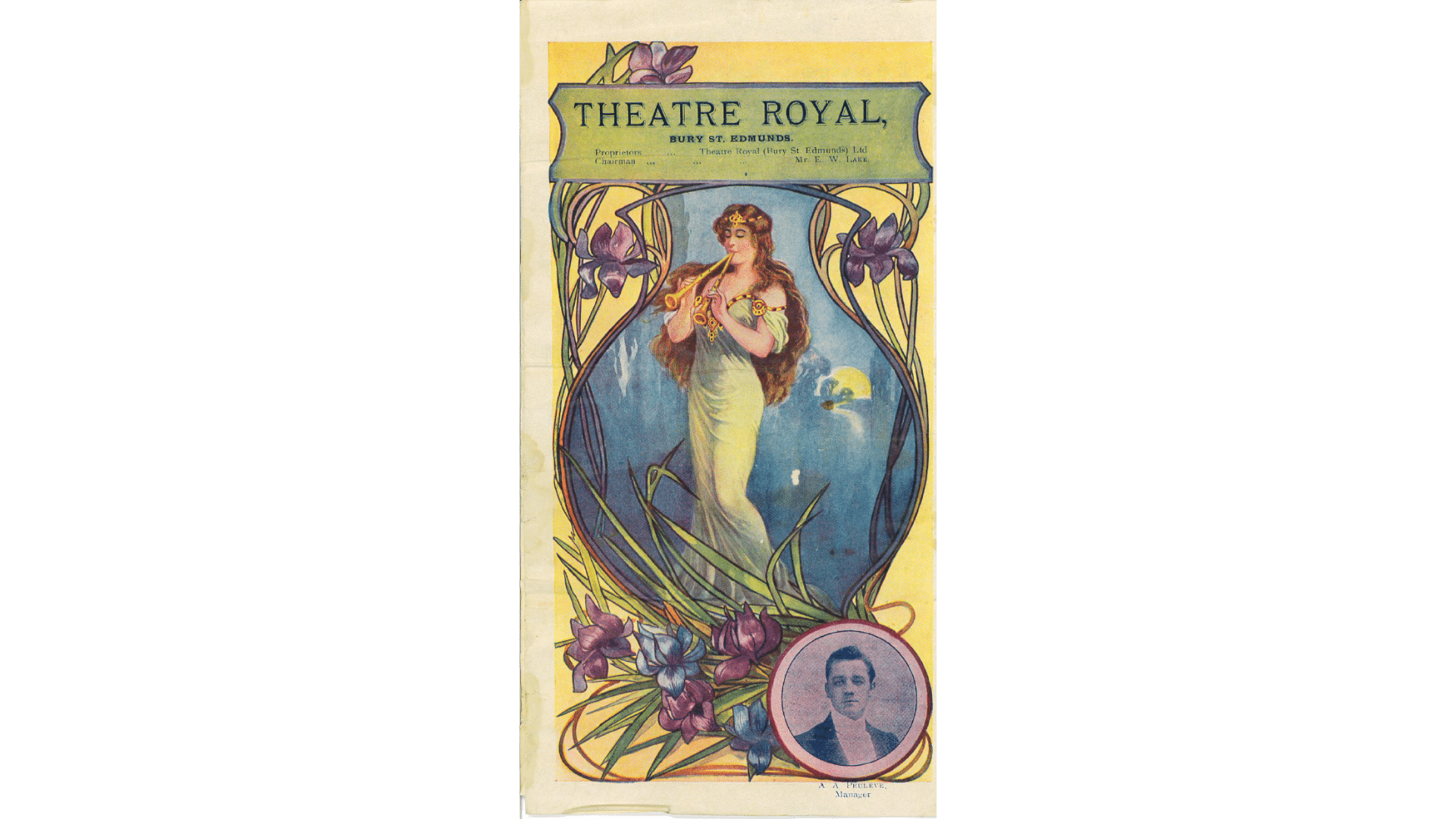

Successive lessee’s aimed to modernise the theatre – this elegant colour programme in a fashionable Art Nouveau style was amongst Auguste Peuleve’s contributions.

1910 Colour programme with inset photograph of lessee Auguste Peuleve,

TRBSE collection

1910

Successive lessee’s aimed to modernise the theatre – this elegant colour programme in a fashionable Art Nouveau style was amongst Auguste Peuleve’s contributions.

1910 Colour programme with inset photograph of lessee Auguste Peuleve,

TRBSE collection

1914

In 1914 Mr Nichols, the new lessee decided to change the name of the theatre to The Royal Coliseum and to show Charlie Chaplin films, dancing and boxing matches as well as theatrical performances. By 1916 the name of the theatre had reverted to the Theatre Royal.

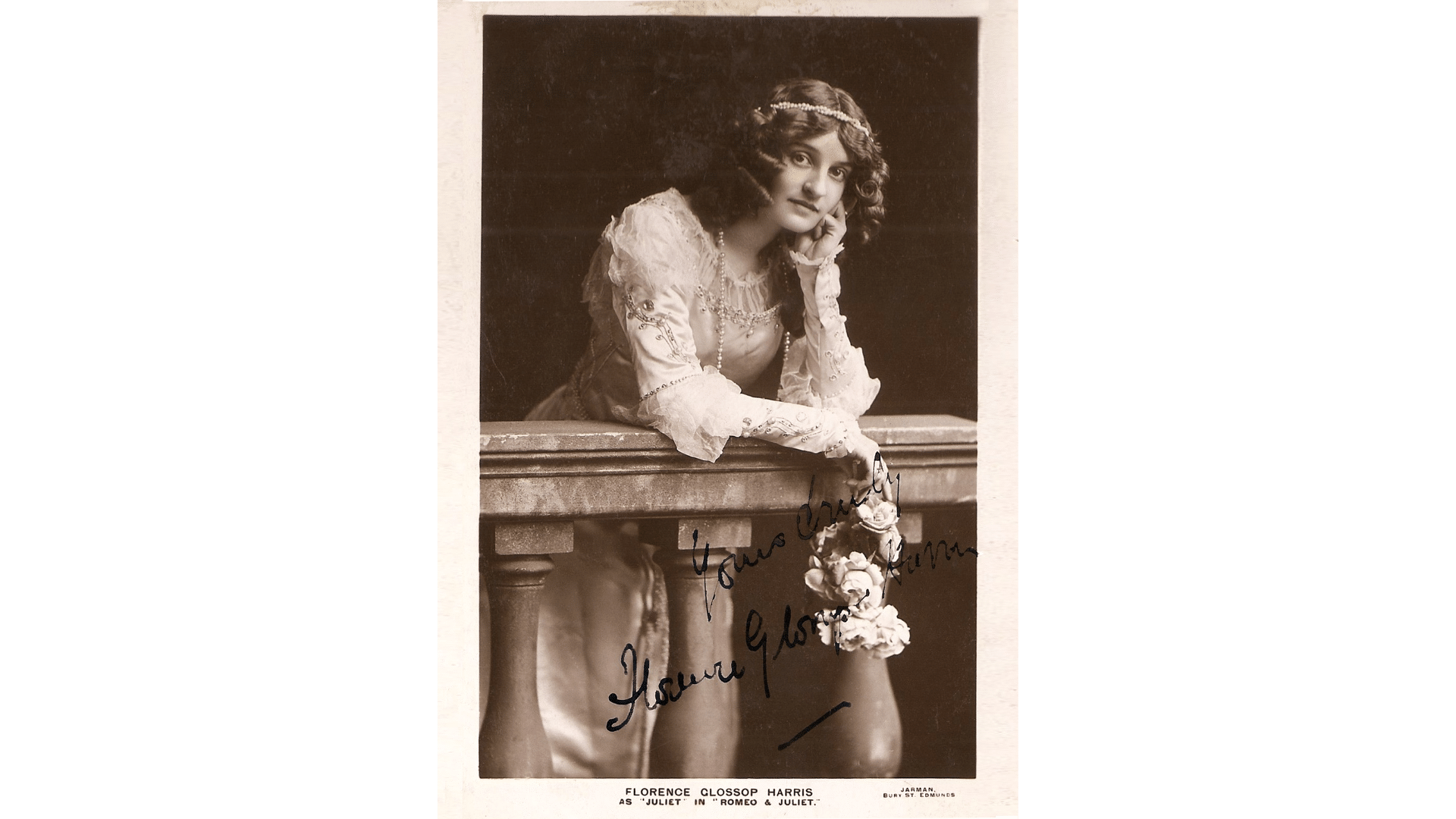

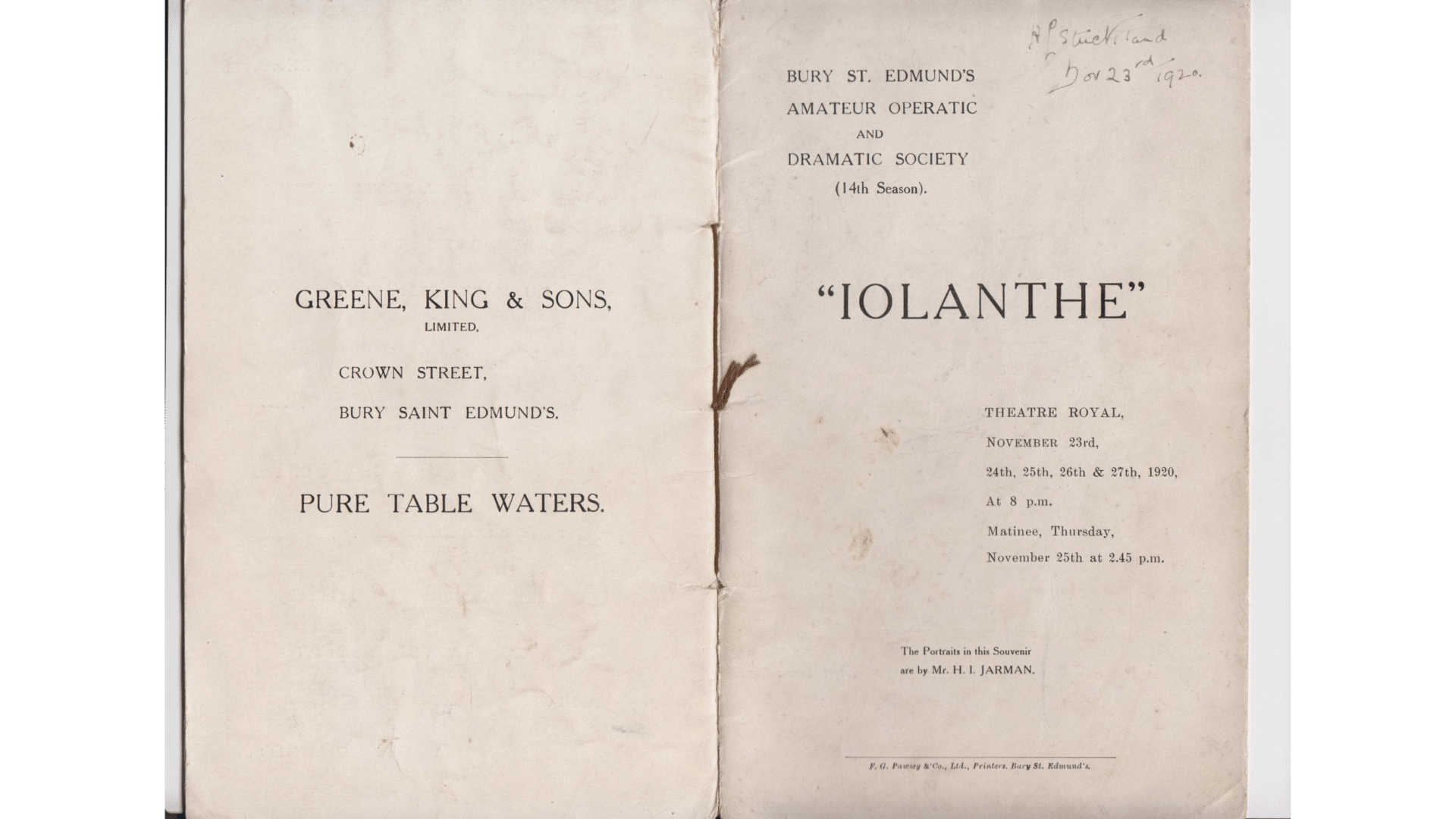

1920

Founded in 1902 the Bury St Edmunds Amateur Opera and Dramatic Society (BSEAODS) performed many times at Theatre Royal and continue to do so today. Amongst their early members was Reginald Hall, whose son Peter was to go on to become director of the RSC and National Theatre. Peter Hall attributed much of his inspiration to Theatre Royal, having broken in as a teenager to see the old theatre whilst it was a barrel store.

1920 Iolanthe Programme

TRBSE collection

1920

Greene King decided to buy the theatre and continue running it until 1925 by which time falling sales have made it financially unviable. On the 30th May 1925 an auction of fixtures and fittings was held in the auditorium. The local paper reported that ‘the stage was covered with numerous articles, from bundles of admission tickets to slabs of scenery… the pair of red plush proscenium sliding curtains and …footlights… [and] grand piano…Never before did such a depressing scene in this old building meet the eye.’

Greene King brewery buy the theatre in 1920

TRBSE collection

c1923

In his spare time, local businessman A.E Henley was a comedian and concert party entertainer. Called ‘the Dan Leno of East Anglia’ after the popular Music Hall star and famous panto dame. Henley’s daughter left the theatre a pair of ‘flap’ shoes, said to have once belonged to Leno which Henley wore on stage at Theatre Royal. The shoes were made by J&E Hallam, a famous firm of clog makers who were awarded a medal at the International Exhibition of 1862.

A.E Henley / Dan Leno’s shoes

TRBSE collection

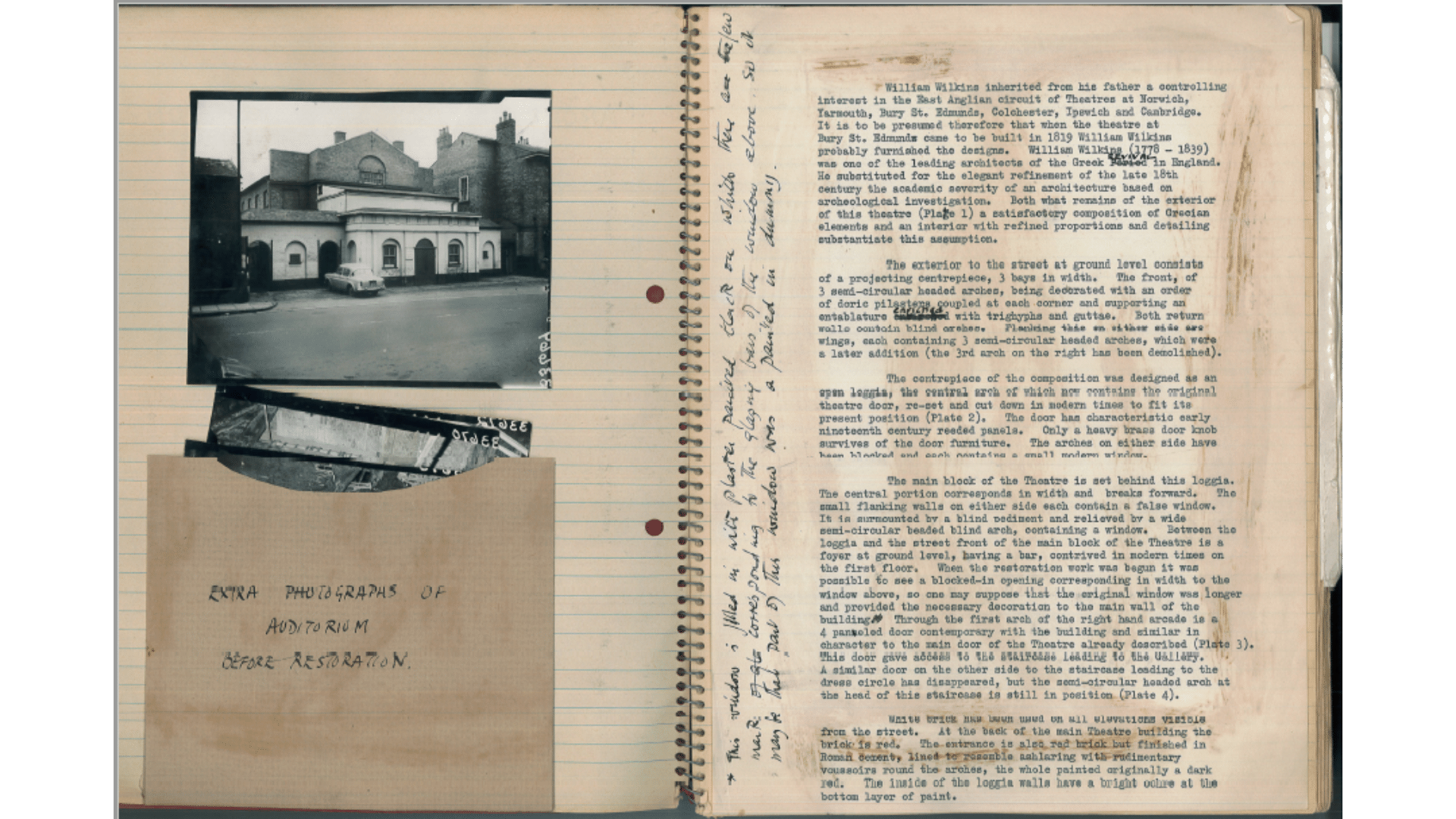

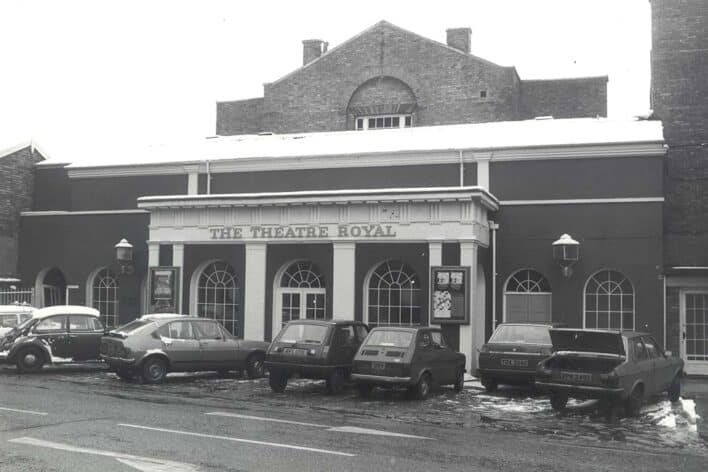

1953

This image shows the exterior of the theatre while in use as a barrel store for Greene King (the façade was painted in the company livery of cream and green). In 1952 the building was Grade listed but a year after this preservation order it was still not watertight.

953 Theatre is Grade 1 listed

TRBSE collection

c1960

Over the years the existence of the theatre was largely forgotten, until a chance conversation between a former actress named Ethel Groat and her friend, county drama co-ordinator Olga Ironside-Wood.

“Three or four years ago we were talking and I mentioned having acted in Bury theatre ,” said Mrs Groat. “Mrs Ironside-Wood couldn’t believe me. She had never heard of any theatre in Bury.” Mrs Groat particularly remembered appearing on stage at Theatre Royal in 1916, because she remembered leaving the theatre after the performance during a Zeppelin raid.

1961

Numerous events were held to raise funds for the restoration of the theatre, from coffee mornings to jumble sales. In 1961 Benjamin Britten held a fundraising concert at Ickworth House in aid of the theatre, issuing unique invitations in the shape of a fan which opened up to form the shape of Ickworth’s famous circular rotunda. Britten was one of several famous cultural figures who lent his name to the restoration advisory panel chaired by the Duke of Grafton. Other panel members included poet and architectural John Betjeman; theatre designer Oliver Messel; actress Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies; architect Hugh Casson; pianist Kathleen Long and director Peter Hall.

1961 Ickworth Concert Fan Invitation

TRBSE collection a Zeppelin raid.

1964

Although the theatre officially reopened on 1st April 1965, the first performance, Noel Coward’s Blithe Spirit took place in May 1964. Although a huge amount of work had been done, the orchestra pit still had a bare earth floor and the musicians had to sit on wooden crates!

1966

‘I was rehearsing and directing one of our first productions, ‘Ghosts’… and I remember putting my spectacles down on the ledge of the dress circle and when I came to collect them later they had gone…. The manager of the theatre scoured the whole theatre and couldn’t find them, he even emptied all the dustbins… a fortnight later I went back to where I had been sitting and there were my glasses in exactly the same place as I had left them. [a colleague] remembers seeing a lady in black sitting in that seat soon after I had vacated it after the play…. Whilst rehearing another play some weeks later I saw a woman in black sitting in the same seat’ but the theatre manager confirmed that nobody had entered the building… On another occasion late at night after a performance, our carpenter and I were sitting in his office when we heard the sound of footsteps coming across the stage and down the stairs, we looked to see but could see nothing. The footsteps came down the stairs and straight through the wall at the bottom and you have never seen two people leave a theatre so quickly’ as we did! There have been a number of reported sightings of this spectral lady – who, at one point attended dress rehearsals so regularly that the theatre manager used to leave a programme on the seat for her!

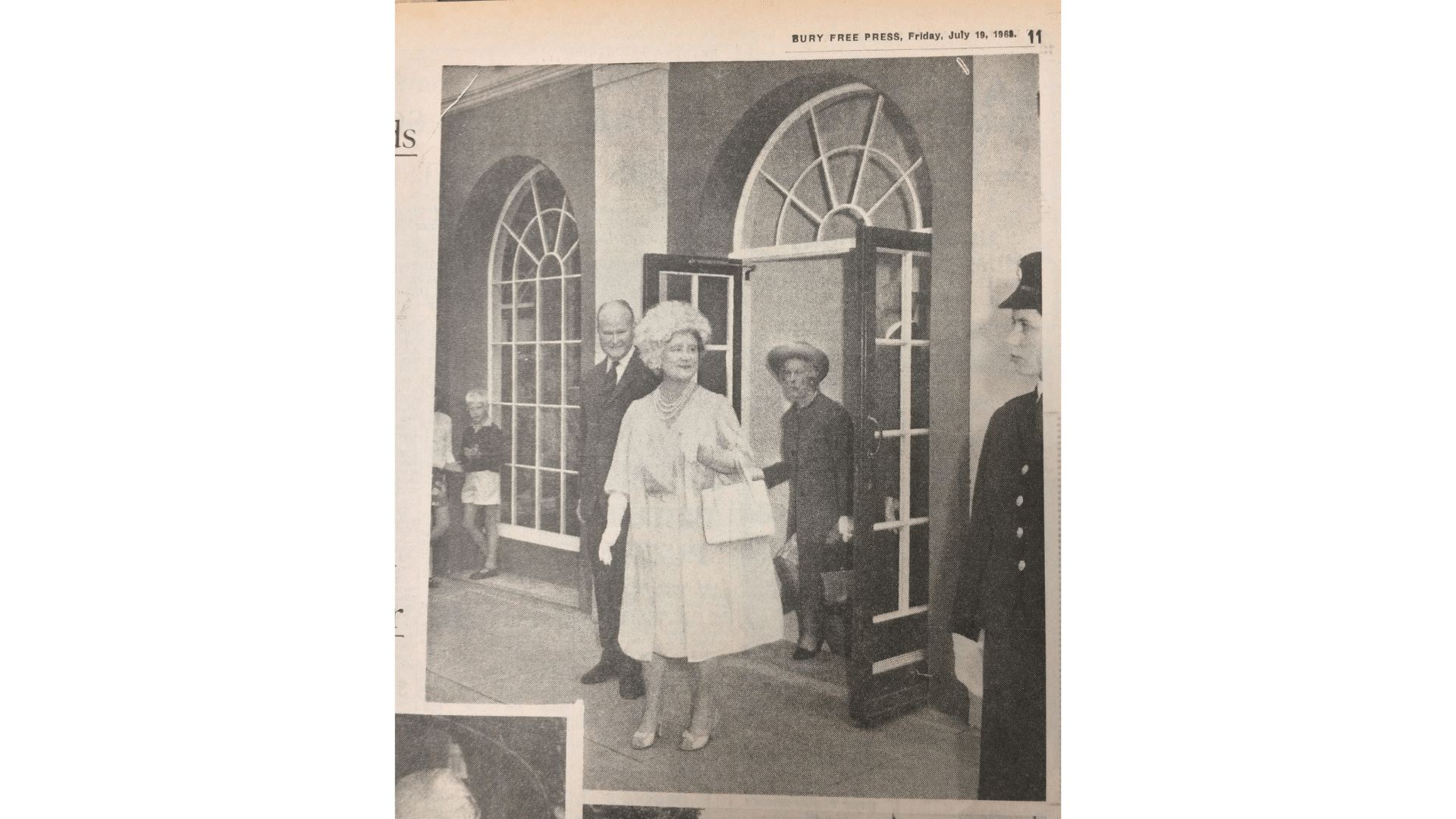

1968

In August 1968 the Theatre received a visit from the HRH Queen Mother, who, along with Princess Margaret had sponsored some seats in the auditorium as part of the restoration appeal. In a somewhat less formal visit, Princess Margaret popped in unannounced some years later to order a quick whiskey at the bar!

Visit of HRH the Queen Mother, 1968

Permission from Kevin Hurst Iliffe Publishing CREDIT: Bury Free Press

2002-2006

In 1822 Oscar and Malvina was the first pantomime to be performed at the theatre; however, it would have borne little resemblance to pantomime today. In the early 19th century pantomimes consisted of two parts; a serious drama and a ‘harlequinade’ using characters derived from the Italian tradition of Commedia dell Arte. These early pantomimes comprised dance, song and slapstick farce, but little spoken word to circumvent the licensing laws, which remained in place until the 1840s. After this point, pantomime became freer, the opening story section of the performance became dominant and writers began to look to other sources, such as fairy tales for inspiration. It was in the later Victorian period that pantomime became particularly associated with a Christmas entertainment for children – largely through the efforts of Augustus Harris, manager of Drury Lane Theatre (and father of Theatre Royal lessee Florence Glossop-Harris) who produced spectacular productions starring famous celebrities of the time. One such was Dan Leno who played one of the first pantomime dames.

Today the in-house pantomime is a highlight of the annual programme at Theatre Royal Bury St Edmunds and proceeds from the show support the work of the theatre for the rest of the year.

2002 Sleeping Beauty Panto Poster

2005-2007

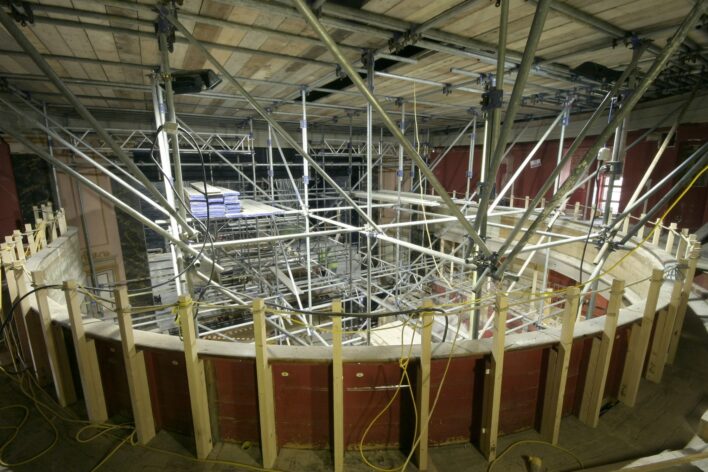

From 2005-7 the theatre received 5.3 million pounds to carry out a major restoration project to restore it to its original Regency grandeur. The funding was provided by the Heritage Lottery Fund, St Edmunsbury Borough Council, Suffolk County Council, Arts Council England, Friends of Theatre Royal, Theatre Royal Foundation, The National Trust and a Public Appeal.

While the theatre was closed it was decided that, in the best theatrical tradition, the show must go on! As such the annual pantomime was performed in a purpose-built big-top tent at nearby Nowton Park.

2005-2007 Pre Restoration

2005-2007

Excavations carried out during the 2005-7 restoration of the theatre unearthed a number of items including oyster shells and clay pipes, which provide an insight into the eating and smoking habits of Regency theatre-goers.

2005-2007 Restoration Clay Pipe

2011

Visit of HRH Prince Charles to celebrate the reopening of Theatre Royal after the renovation.

2011 HRH Prince Charles

HRH Prince of Wales at Theatre Royal Bury St Edmunds04/03/11 Copyright: Keith Mindham Photography 2011. Licence to use: Theatre Royal press & marketing only. You can not sell or licence these images for use to any other organisation or person.

2019

With the support of the Heritage Fund, Theatre Royal celebrated its 200th anniversary in style throughout 2019. The year started with the launch of the newly renovated Peter Hall Room as a space for education and exhibitions and a series of new tours, including the interactive Close Encounters Tour in which visitors had the chance to meet some of the fascinating figures from our past. The summer saw the unveiling of our new mosaic, the culminative work of students from six local primary schools in collaboration with Rojo Arts and rehearsals of the young company ready for a very special production of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

We held events for people interested in tracing their theatrical ancestors and lectures about the history of the theatre along with ghost tours -something for everyone!

Account

Account